Wednesday, 10 November 2021

New book by our new network Chair coming soon

Monday, 8 November 2021

New collection of primary sources

Nineteenth Century Crime and Punishment

Friday, 8 October 2021

New Historical Criminology book

History & Crime: A transdisciplinary approach.

Thursday, 13 May 2021

New book on police reform

Provincial Police Reform in Early Victorian England: Cambridge, 1835-1856

Provincial Police Reform in Early Victorian England: Cambridge, 1835-1856, published by Routledge, is the latest addition to the longstanding debate on the genesis of the ‘new’ police in England. As the blurb explains, the book examines ‘the process of police reform, the relationship between the police and the public, and their impact on crime in Cambridge’.

Further information on the book, together with a discount code, are available in the flyer below..

Monday, 10 May 2021

100 Years of the Infanticide Act: Legacy and Impact

Call for abstracts and titles.

"The collection will focus on the impact, legacy, and future of the infanticide law, starting with its enactment in 1922 and focusing on the current law as found in the Infanticide Act 1938. We are interested in receiving contributions which consider the infanticide law in England and Wales and in other jurisdictions from doctrinal, theoretical, socio-legal, medico-legal, and legal history perspectives.Our intention is to bring together a range of scholars who have made important contributions to our understanding of this law. This includes scholarship from across the globe that engages with the criminal law and criminal justice responses to infanticide in other jurisdictions, whether they have enacting specific legislation on this issue or taken a different approach.In particular, we are interested in contributions which consider (but are not limited to) the following issues:

- How the infanticide law has been interpreted and used as part of the criminal justice response to women who kill their babies

- Theoretical and doctrinal analyses of the offence/defence of infanticide

- How the infanticide doctrine fits in with and relates to the broader framework of capacity-related criminal defences

- Evidential issues arising from the use of the infanticide law

- The future outlook for this law, particularly with regard to considerations for abolishing or reforming it

- Medico-legal critiques of the medical rationale of the law

- Feminist critiques of the law

- Infanticide laws (or lack thereof) in other jurisdictions

We have interest from and are working with Hart Publishing to develop a book proposal. The editors warmly welcome submissions from academics and researchers, as well as legal professionals. Please submit a 200-word abstract of your proposed chapter to emma.milne@durham.ac.uk on or before May 31st 2021. We will be asking authors to work to the following deadlines:

Deadline for abstracts

End of May 2021

Informal online workshop to present chapter focus

September 2021

Author first drafts due

End of March 2022

Final chapters (following editorial review) due

June 2022

Wednesday, 20 January 2021

Feminist Perspectives on Women's Violence

Call for Abstracts.

Saturday, 16 January 2021

Path dependencies and criminal justice reform

Call for abstracts.

Thomas Guiney, Ashley Rubin and Henry Yeomans have issued a call for abstracts for a special issue of the Howard Journal of Crime and Justice on ‘Path Dependencies and Criminal Justice Reform: Investigating Continuity and Change across Historical Time’.

This issue – which arises out of a workshop held at the #HCNet virtual event last year – aims to explore the theoretical potential of ‘path dependency’ to explain institutional stability, incremental reform, and periods of rapid policy change in criminal justice.

Submit an abstract (300 words) and short biography (100 words) by 5 March 2021 to: tguiney@brookes.ac.uk; atrubin@hawaii.edu; and h.p.yeomans@leeds.ac.uk. The organisers plan to hold a virtual symposium in November 2021 to discuss draft papers, ahead of submission for peer review in February 2022.

Monday, 7 September 2020

New book by Dr Alexa Neale

Photographing Crime Scenes in Twentieth-Century London

Friday, 4 September 2020

States, People, and the History of Social Change

New Book Series

McGill-Queen’s University Press has announced the launch of a new book series which aims to bring together cutting-edge work on the history of criminal justice, welfare and other areas of social change and social policy.

Edited by Rosalind Crone and Heather Shore, works in the series will explore how people have negotiated the use of state power, and what social consequences have followed from state efforts to regulate, improve and otherwise shape people’s lives.

The series welcomes international scholars whose research explores social policy (and its earlier equivalents) as well as other responses to social need, in historical perspective.

Titles under advance contract in the series include #HCNet members. See the flyer for more details:

Monday, 31 August 2020

Marginalised Voices in Criminology

Call for Chapters

Kelly Stockdale and Michelle Addison have issued a call for chapters to contribute to a planned edited book: ‘Marginalised Voices in Criminology: Theory, Criminal Justice, and Contemporary Research’.

This inter-disciplinary and international collection seeks to engage with discussions and debates around power, colonialism, and identity, and how the criminological curriculum (re)produces doxa grounded in hegemony and privilege.

Authors interested in contributing should submit a 250-word abstract to kelly.stockdale@northumbria.ac.uk by 30 October 2020.

More details are provided in the full call, available to download or view below.

Sunday, 30 August 2020

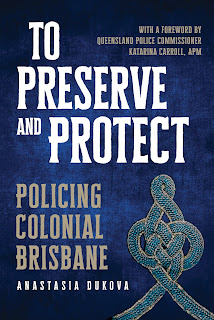

New book by Dr Anastasia Dukova

To Preserve and Protect: Policing Colonial Brisbane

Thursday, 11 June 2020

Call for Papers: Legacies of Empire

Punishment and Society Special Issue

Submissions are sought for a special issue of the journal Punishment and Society, to be titled ‘Legacies of Empire’.

The Guest Editors say:

The special issue will examine the global legacy of empire and colonialism through its effects on the penal regimes and practices of former colonies. Submissions are sought which explore the historical patterns of penal journeys as well as the contemporary legacy of many of these phenomena, including the aftermath of colonial policies on Indigenous communities. Contributions are sought from history, sociology, law, and criminology, capturing interdisciplinary work in which the concept of ‘empire’ is broadly conceived, and which contribute to the field of punishment and society (e.g. through literature, theory, empirical material).

For scholars of crime and punishment, greater commitment than ever is necessary to engage with perspectives that critique the times in which we live. The intention of this special issue is to further the democratization of criminological knowledge and to create a space for voices which embrace southern criminological and postcolonial perspectives. We particularly welcome submissions from scholars based in the Global South.

Abstracts of 500 words should be sent to the guest editors (email below) by 15th August 2020. Submissions are received on a competitive basis and will be reviewed by the guest editors. A selection will be accepted and the full manuscript subject to peer review (deadline for submission of final manuscript TBC with contributors at a later date).

Guest editors:

Lizzie Seal (University of Sussex, UK)

Bharat Malkani (Cardiff University, UK)

Lynsey Black (Maynooth University, Ireland)

Florence Seemungal (University of the West Indies Open Campus, Trinidad and Tobago)

Roger Ball (University of Sussex, UK)

|

| Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (undated, author unknown) via pxfuel.com |

Wednesday, 10 June 2020

Call for contributions: Times of Crisis

BSC Summer Newsletter

|

| 'Hong Kong Protests 2014' by taichi87 via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA |

Tuesday, 9 June 2020

New book series launched

Emerald Advances in Historical Criminology

|

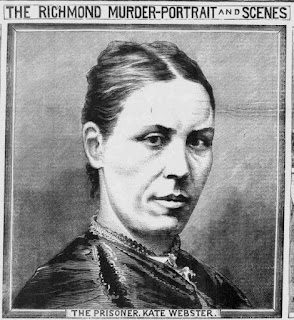

| Illustration from John Reynolds, Triumphs of Gods Revenge and the Crying and Execrable Sin of (Wilful and Premeditated) Murther (London: A.M. for William Lee, 1670) via Public Domain Review. |

Monday, 8 June 2020

New book published on history of private security

Private Security and the Modern State

|

| Book cover, copyright Routledge 2020 |

Wednesday, 19 February 2020

Public talk at Northumbria University

“13 yards off the big gate and 37 yards up the West Walls”: Crime scene investigation in mid-nineteenth-century Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Helen Rutherford and Clare Sandford-Couch will be sharing their research on the history of forensic investigation in Newcastle. They say:

“We have recently published on role of the uniformed police in crime detection in connection with a murder case in Newcastle in 1863, and are currently researching the role of the police in gathering evidence in a murder case from 1838. Our research into nineteenth-century policing in Newcastle indicates a level of sophistication in policing and a methodical, almost scientific, approach to crime scene analysis far earlier than has previously been appreciated.”

Network members may also be interested in a public lecture at Northumbria University by Professor Carole McCartney on 25th March 2020 titled 'The Forensic Science Paradox'. For more information visit the Northumbria University Events pages.

|

| Forensic Ornithologist Roxie Collie S. Laybourne (1912-2003) identifying bird feathers (c) Smithsonian Institution via Flickr. |

Friday, 14 February 2020

Recent publication featuring #HCNet authors

Crime and the Construction of Forensic Objectivity from 1850

Crime and the Construction of Forensic Objectivity from 1850 features twelve chapters, including an excellent introduction by Professor Adam which draws out the significance of the historical development of forensic knowledge to a variety of contexts. Two centuries, six countries and multiple disciplines are represented in the edited collection which is published by Palgrave MacMillan as part of their Histories of Policing, Punishment and Justice series.

Some of the chapters develop ideas presented at past BCHS conferences, while others introduce new subjects. Several #HCNet members are among the chapter authors, including Angela Sutton-Vane who won the Clive Emsley Prize for the best postgraduate paper at BCHS 2018.

A list of the book chapters and authors is included below.

The CFP deadline for the next BCHS is 8th April 2020. More about the event here.

Contents

Crime and the Construction of Forensic Objectivity from 1850: Introduction

Alison Adam

Forensic Representations: Photographic, Spatial, Dental and Mathematical

Bodies in the Bed: English Crime Scene Photographs as Documentary Images

Amy Helen Bell

Murder in Miniature: Reconstructing the Crime Scene in the English Courtroom

Alexa Neale

The Biggar Murder: ‘A Triumph for Forensic Odontology’

Alison Adam

Making Forensic Evaluations: Forensic Objectivity in the Swedish Criminal Justice System

Corinna Kruse

The Professional Development of Forensic Investigation

The Police Surgeon, Medico-Legal Networks and Criminal Investigation in Victorian Scotland

Kelly-Ann Couzens

‘13 Yards Off the Big Gate and 37 Yards Up the West Walls’. Crime Scene Investigation in Mid-nineteenth Century Newcastle upon Tyne

Clare Sandford-Couch, Helen Rutherford

The Construction of Forensic Knowledge in Victorian Yorkshire: Dr Thomas Scattergood and His Casebooks, 1856–1897

Laura M. Sellers, Katherine D. Watson

Reporting Violent Death: Networks of Expertise and the Scottish Post-mortem

Nicholas Duvall

The Media and Ethics in Constructing Forensic Objectivity

Detecting the Murderess: Newspaper Representations of Women Convicted of Murder in New York City, London, and Ireland, 1880–1914

Rian Sutton, Lynsey Black

‘Children’s Lies’: The Weimar Press as Psychological Expert in Child Sex Abuse Trials

Heather Wolffram

Murder Cases, Trunks and the Entanglement of Ethics: The Preservation and Display of Scenes of Crime Material

Angela Sutton-Vane

|

| Book cover (c) Palgrave Macmillan |

Thursday, 13 February 2020

The Uses of Historical Criminology: Guest posts

Replies to Churchill, Lawrence and Yeomans

In two guest posts for this site, #HCNet members Tom Guiney and Vicky Nagy offer their reflections on the articles and on future directions for Historical Criminology more broadly:

- Historical criminology, theory building and the importance of social ontology

- Historical Criminology and Southern Criminology by Vicky Nagy

Historical Criminology and Southern Criminology

by Victoria Nagy, University of Tasmania

In a recent issue of Criminology and Criminal Justice the possibilities of historical criminology were well articulated by Henry Yeomans, David Churchill and Paul Lawrence. To see three articles devoted to the building of theory in historical criminology is gratifying; it is a benefit for those who champion it, and it speaks to those criminologists who may not yet be sold on the benefits of an anchoring in history.

This blog post isn’t a review of the three pieces per se but an addition to the conversation about historical criminology started so well by the thematic section in C&CJ. This involves bringing the Global South into the discussion. The uniqueness to the Global South is what is often missing in criminology and from the theorisations of historical criminology in C&CJ’s thematic issue.

Recently Australian, New Zealand, South American, South East Asian and South African criminologists have been turning attention to the questions of where knowledge is created, who it benefits, and how relevant it is to those living in the Global South. This new theoretical branch of criminology is termed Southern Criminology and employs southern theory (Connell 2007) to consider the power relations embedded in the production of criminological knowledge and how traditional criminology ‘privileges theories, assumptions and methods based largely on empirical specificities of the Global North’ (Carrington, Hogg and Sozzo 2016, 1). The aim of Southern Criminology is not to fragment the field further into those who do southern theory versus those who do not; rather it makes the argument that there is a need for a transnational criminology that is inclusive of the Global South (Carrington et al., 2016; Hogg, Scott and Sozzo 2017; Travers, 2019). As Carrington et al (2016) put it, it is about de-colonising and democratising criminological knowledge.

This leads us back to the articles in C&CJ. The discussions in this thematic issue read as very Global Northern-centric. This in and of itself is not a problem, and it is not surprising seeing as the social sciences as a field are dominated by the Global North: most publishing houses, journals, and conferences that direct how we think about and do social science are located either in the UK or the US (Graham, Hale and Stephens 2011; Carrington, Hogg, Sozzo and Walters 2019). The way in which criminology (and arguably history) has operated has also tended to assume that a relocation of theory was all that was needed, especially with countries such as Australia and New Zealand. For example, well-meaning reviewers have oftentimes outed themselves as not being from either Australia or New Zealand when requesting the use of British laws or examples that have no relevance to either southern colony but are considered fundamental if one views criminology just from a northern perspective. This does not mean that Australian and New Zealand criminologists are immune from this. There is still a tendency for the theories generated in the North to be picked up and transplanted here in the South thereby ignoring the history and context of the south while evidence is procured to support of these northern theories (Connell, 2014; Carrington et al., 2016).

The history of the Global South is closely interwoven with the Global North. Churchill (2019) rightly points out that our discussions of history as stadial are limiting to how we can do historical research in criminology and there is a perfect example of this in practice. For both Australia and New Zealand, indeed for all of the Global South, history is not in the past but here and now for the people who were colonised by those in the Global North. History has bled into the present through the over-representation of indigenous people in our criminal justice systems. Intergenerational trauma originating from colonisation by the British plays no small role in the poverty, oppression and violence experienced by Australian Aboriginal communities today (Funston and Herring 2016). Discussing the flow of history must go beyond a discussion of flow of multiple dimensions past and present and consider the flow from north to south as well.

For those of us working in historical criminology, Lawrence’s (2019) argument that the past can be used to explain the present in a long-term fashion and that historical data can be an immense support to criminologists today is one we’d all agree with. However, how or what parts of the past are used is important to consider. The violence that was used to subject the rightful owners of these lands in the Global South to their colonisers did not appear in official records. Only the most egregious example of colonist violence appears in our social or legal records, and once the frontier wars in Australia came (somewhat) to an end in the early twentieth century that violence continued in acts such as the forceable removal of Aboriginal children from their families which led to the Stolen Generation in Australia and the intergenerational trauma mentioned above. It is only with mapping the effect of the frontier wars in Australia, for instance, that we’re starting to see emerge the level of devastation wrought on this country by colonisers. Dispossession, bloodshed, and genocide of indigenous peoples cannot be so easily translated or understood by criminology if we do not accommodate it in our data collection and analysis (Carrington et al 2016).

And finally, Yeomans (2019) makes a strong case for the creation of a more “historically sensitive criminology” (p.456) that is three-dimensional, but that cannot be done without understanding that the history of these colonised nations in the Global South is not settled, nor does it manifest in a way seen in UK, US or other northern criminologies. Arguably the Global North where the criminological theories were developed at a time of peace is not reflective of the experiences of many in the Global South who were at the same time experiencing genocide and struggling for democratic freedoms from colonisers or dictators, and these criminological theories presuppose that crime is an urban phenomenon where disorganisation was changing the face of the urban landscape with rural locations as “naturally cohesive” spaces (Carrington et al. 2016).

So what does this mean? It doesn’t mean that Southern Criminology is better than other criminology theories for those of us in the Global South but rather that we need to ask what can be done to ensure that the emerging branch of historical criminology and discussions of its theory is democratic and decolonised.

Historical criminology, theory building and the importance of social ontology

A (short) reply to Yeomans, Churchill and Lawrence by Thomas Guiney, Oxford Brookes University

A detailed review of these contributions is beyond the scope of this blog post. However, in a follow-up comment piece for the British Society of Criminology, the authors helpfully distil their position down to three cross-cutting propositions with regards to the value of historical research in criminology:

• First, that criminology is preoccupied with the present and new developments.

• Second, that the past is frequently presented in overly reductive terms in order to establish the novelty of the present.

• Third, that a long-term perspective can yield new insights on contemporary crime and justice.

When taken as a whole the authors express hope that the thematic edition will, ‘provide some foundations for more sustained engagement with historical approaches, perspectives and data in criminology, and thus help pave the way toward a more fully historical criminology.’

In this short reply, I want to suggest that while the authors make a very significant contribution to the first plank of this important project, they do not entirely succeed in their aspiration to promote a more fully historical criminology.

By focusing almost exclusively on epistemological concerns – of definition, measurement and classification – the authors side-step a series of current debates in social ontology which animate, and give texture to, history, time and temporality in criminological perspective.

As I have argued elsewhere, the positions we occupy within the structure and agency debate, the relative merits of materialism and idealism or the extent to which a distinction can, and should, be made between the ‘appearance’ and ‘reality’ of things continue to do much of the conceptual heavy lifting within accounts of crime and criminal justice (Guiney, 2018).

By downplaying these areas of contestation in the pursuit of a cleaner inter-disciplinary exchange, my worry is that we risk inadvertently collapsing historical criminology into history. That we lose sight of what is distinctive and complimentary about the criminological scholarship.

This would be a misstep in my view. As Sewell has argued theory building ‘has a strikingly less central place in history than in the social science disciplines’ (Sewell, 2006: 3) and criminology – a ‘rendezvous discipline’ with a longstanding tradition of theoretical exchange and methodological innovation – can greatly enrich both the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of crime and criminal justice.

While we may agree that a ‘three-dimensional criminology’ should attend to the linkages between questions, forms and functions (Yeomans, 2019: 467), these analytical choices surely present a series of parallel ontological considerations. Agent-centred accounts of political elites and grass-roots activism may be well calibrated to the rhythm(s) of everyday life, but institutional norms and social structures often come into focus when societal change is located within a broader historical perspective.

There may be very good reasons to reject a ‘stadial’ view of history, which reduces social change to a series of transitions from one settled stage of human development to another (Churchill, 2019: 478). But does this not demand some critical engagement with the forces which mediate the continuities and dislocations of a pluralized conception of historical temporality? Should historical criminologists focus their analytical gaze upon the genius of those who seem able to bend history to their will, or seek out the invisible hand of shifting material interests?

If long time-frame analysis over several centuries is ‘the only robust means by which to evaluate the potential of the past to help explain the present’ (Lawrence, 2019: 494) does this not imply that historians have access to a deeper, or more complete view of reality, than those who live through such events? If so, what is the nature of this reality and what general laws govern the long sweep of history – a civilizing process? Historical materialism? A whiggish belief in progress?

These lines of enquiry go largely unexplored. Yes, history matters. But a confident, reflexive and fully historical criminology is also one that embraces theory building and the inherent contradictions of social ontology.